Social media, I can confidently assert, is dead. We’ve just got to wait for the 4.2 billion people or so using it to realise it and leave, preferably helping with the washing up as they do.

OK, so it’s not exactly dead, but at least it’s dead as a term. It’s only been around since 2009, but if we look closely it has long stopped meaning what we meant it to mean. Originally we talked about Web 2.0, which most of us old enough to remember it defined as anything that shed the old paradigm of static web pages, the dot.com world dominated by blow-out companies, and instead focused on user-generated content — meaning helpful blogs, videos, forums and chitchat.

Social media was initially a subset of Web 2.0, insofar as any of us ever thought about it; it meant those parts of the web where the focus was on individuals sharing updates with each other, of making the flatter but still somewhat static blog world more interactive, collaborative. (Twitter is still sometimes called a microblog, which gives you and idea of the connective tissue between blogging and what we now think of as social media. And in some ways the growing passion for threads is an indication of that relationship.)

But when Google, and later Facebook, needed to monetise themselves, Web 2.0 pivoted from being a largely profit-free environment to being a mercenary one, where users’ personal data became the fungible asset, converted by the platforms into money by leasing highly targeted space for ads.

We all know the story of that, and what happened next: social media platforms grew impressively. But what we perhaps don’t fully understand yet is that in so doing, they are no longer ‘social’ or ‘media’. Since the requirement from a monetary point of view is to hold the attention of the user for as long as possible — so they can see as many ads as possible — the goal is not to create ‘media’ that is ‘social’, but to create a highly personal experience, one that is hard to let go of. This used to mean just stuff that was interesting. Now that is seen as rather quaint.

It’s now about triggering whatever desires, impulses, fears we have and latching on to those. In the words of Charlie Brooker, it’s a place where emotions are heightened. But (and these are my words) where those emotions are never quite resolved. It’s no good creating a feeling where the user is happy enough, satisfied, because then they’ll put their phone down, walk away and do something else. The goal, as Adam Curtis explains in his latest series of films, Can’t Get You Out of My Head, is to foster anxiety, that something’s not right, unsettled, because that will keep the user hooked.

Facebook (and the others, though nearly half of interactions on mobile were on Facebook and Google properties five years ago (PDF).) also don’t want you clicking on links and going away from the site to read something because chances are you won’t come back. Endless, infinite scroll, is the goal. (Infinite scroll is now 15 years old, which gives you some idea of how long we’ve been on the hamster wheel. Its inventor, Aza Raskin, has since disowned the technology, describing it and similar approaches as ‘behavioural cocaine.’

There’s another element, also identified by Charlie Brooker: it’s the idea of social media as performance. Part of the strategy behind social sites is to make you feel somewhat inadequate, to create a sense of dissatisfaction, as part of that addictive anxiety — what we often hear called Fear of Missing Out, or FOMO. Sure, there are lots of smileys, hugs, kisses on there, but I don’t need to tell you these are not real. What is real, though, is the desire to get approval.

On social media there’s no point in telling people what you’re doing, how you’re feeling, or where you are if none of those are particularly interesting or exciting. Mundanity doesn’t cut it on social media. So you need to perform, to present the most entertaining or interesting side of yourself, however fleeting and inauthentic that is: most of the time this means finding that rare moment when your family’s not fighting or the kids are not ripping down the curtains to post a portrait of domestic bliss. Or add a filter or two to make you, or your background, look better.

This is not performance art, it’s performance anxiety. You need to project an exaggerated, or even opposite, version of yourself — happy usually, but it can be sad if the emotion is one to which others can respond — because this is what social media demands. And that’s the way to get likes. Which means being noticed. Social media has made us believe that only if we get likes and comments on our posts do we exist. ‘Social’ here means that we have to be social beings, because the alternative — not posting, or posting and not attracting likes — is anti-social, or social failure.

And that brings us to another aspect, that I am brazenly lifting from Charlie Brooker: because of this need to perform on Twitter (and Facebook for that matter), are games. He describes Twitter thus: a “multiplayer online game in which you choose an avatar and role-play a persona loosely based on your own, attempting to accrue followers by pressing lettered buttons to form interesting sentences”.

The same is true of Facebook, in slightly different ways. The platforms are designed in the same way: “There’s a clear gameplay loop where, the more you engage, the less you want to put it down. If Twitter didn’t already exist, you could launch it today on the Steam game store as an RPG.”

He’s absolutely right. Social media is no longer a way to share and interact with your friends or connection in a cozy, caring environment — if it ever was. It’s a game, a competition. Even if you don’t think it is, it is. Even if you’re not actually contributing, just reading it is. It is because if you don’t participate and just scroll, you quickly develop a sense of unease, a sort of dystopian trance, where you’re consciously or subconsciously comparing your own life, or your own intelligence, with those you’re reading or flicking through. The political upheavals of the past few years have only made this worse — what has become called ‘doom scrolling.’

The platforms encourage this, are, indeed, designed for this, because they need to trap you into a ‘state of emotional motion’, where you’re always restless, always uneasy, always thinking that perhaps one more post, one more status update by someone, will snap you out, lift you back up to a mental state to face the rest of the day. And if you’re posting stuff, or hoping to, then that existential unease is compounded, because you will now expect the platform — your friends, connections or whatever — to acknowledge your existence by adding likes. But how many is enough? And do you respond to the comments? The treadwheel is merciless.

Charlie Brooker is right. Social media has essentially been gamified. It has ended up meeting its arch enemy for attention — online games — in the middle. This is not surprising: games have always grabbed the most attention. (In 2019 69% of U.S. consumers said they would rather give up social media apps or TV than lose their favorite mobile games, according to a study by mobile ad firm Tapjoy.)

Online games have become social networks (think Roblox and Fortnite) while social networks have become games. Essentially they’re all the same thing. Whatever it takes to keep you hooked. A rhythmic flow of user-generated content lures us in, and hopes we will participate. But even if we just scroll, we’ll never reach the bottom. It will keep on going because to do anything else would be to lose us — possibly forever.

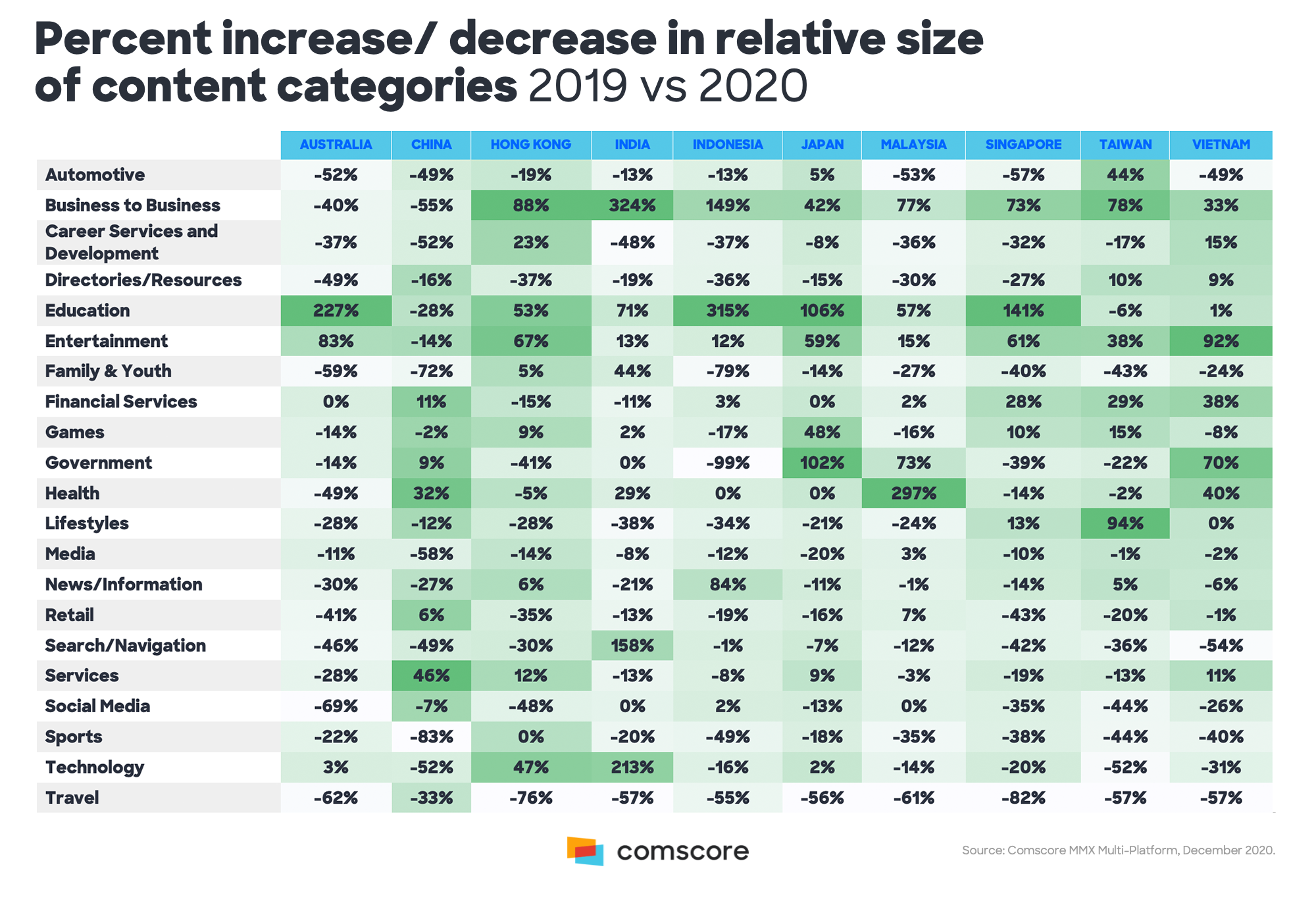

That, I suspect, is already happening. A detailed look at Facebook daily active users shows numbers in North America have largely been flat for the past year. Europe is little better. The only real growth is coming from APAC and the Rest of the World. And even there, data released today by comscore shows that social media usage fell relatively across most of APAC in 2020 vs 2019. (Entertainment, games, government and health were the biggest gainers, naturally enough, given COVID.)

It’s being supplanted by newcomers like TikTok, which are much more creative — and honest — in their approach towards hooking you. Post something short to drive likes and keep attention. There’s no pretence at building a social, and sociable, environment. Instead it’s about response and reward. Social media, in something like TikTok, has already demonstrated that it’s has moved on, and is much closer to gaming than it is to old fashioned social networking.

Meanwhile those tools that are purely focused on social networking — like Clubhouse, for example — are thriving. Yes, they still have strong elements of performance built in, but the content itself is a mostly collaborative one, by talking in a room, and do not appear at least on the surface to be designed to exploit feelings of unease, dissatisfaction, need for validation or a sense of inferiority.

So it’s not as if social media has actually died. What we think of as social media, the second tranche of sites like Facebook (the first were things like MySpace and Friendster) have morphed into games to retain attention. The result is that the most ‘social’ aspects of such sites, like Groups, have become separate islands in themselves. Indeed, the original principles and potential of social media has shifted back to the world that predated Web 2.0: instant messaging. This has been around since ICQ, launched in 1995, though messaging itself dates back to the early 1960s. Include teleprinters in that and we go back to the 1840s. WhatsApp helped popularise the concept on mobile, effectively killing off SMS (which has been in decline since 2012) and blurring the boundaries between computer-based messaging and mobile messaging. By March 2020 WhatsApp was not that far behind Facebook in terms of monthly active users — 2 billion vs Facebook’s 2.6 billion (when you take into account that. It’s no surprise, then, that Facebook has been forced to connect its messaging apps because of this shift: Facebook messenger has a paltry 1.3 billion users, and Instagram 1 billion. )

Bottom line? A lot of attention has been given to the sharing of information, and misinformation, on social media. I would suggest looking beyond that, to look at why people post, or feel the need to post, and argue that it’s the inbuilt addictive, gamification-driven, intent of social media companies that is the larger problem. Simply put, the more time people spend on social media, the more likely they’re going to be emotionally unsettled, more susceptible to anti-social — for example fake, but also inciting — content. I don’t blame the social media companies entirely for this, but it’s tempting to conclude that if they were building systems that had a definite end-point: ‘OK, you’re up to date! Go outside and play with your kids!’ there would be a lot fewer of us stuck down rabbit holes. And social media wouldn’t have an expiry date on it.