How we shoot and watch video is changing, and with it the way we engage with the world

The two iconic images of the fall of Kabul involve a C-17 taking off from Hamid Karzai Airport. It’s as searing as the helicopter perched atop an apartment complex in Saigon, a stream of Vietnamese climbing the ladder to the roof in the hope of getting aboard:

In Kabul, 46 years later, we have something similar, but now the photographer is not a UPI photographer called Hubert Van Es, back at the office developing film:

If you looked north from the office balcony, toward the cathedral, about four blocks from us, on the corner of Tu Do and Gia Long, you could see a building called the Pittman Apartments, where we knew the C.I.A. station chief and many of his officers lived. Several weeks earlier the roof of the elevator shaft had been reinforced with steel plate so that it would be able to take the weight of a helicopter. A makeshift wooden ladder now ran from the lower roof to the top of the shaft. Around 2:30 in the afternoon, while I was working in the darkroom, I suddenly heard Bert Okuley shout, “Van Es, get out here, there’s a chopper on that roof!”

I grabbed my camera and the longest lens left in the office — it was only 300 millimeters, but it would have to do — and dashed to the balcony. Looking at the Pittman Apartments, I could see 20 or 30 people on the roof, climbing the ladder to an Air America Huey helicopter. At the top of the ladder stood an American in civilian clothes, pulling people up and shoving them inside.

After shooting about 10 frames, I went back to the darkroom to process the film and get a print ready for the regular 5 p.m. transmission to Tokyo from Saigon’s telegraph office. In those days, pictures were transmitted via radio signals, which at the receiving end were translated back into an image. A 5-inch-by-7-inch black-and-white print with a short caption took 12 minutes to send.

It’s beautifully framed, the chopper and the building, with its tiny shack on the roof, the empty space in the upper right of the screen, the eyes drawn up the rising tide of humanity towards the diplomat in his shirt sleeves, either reaching to help or reaching to hold back, we are unsure. We want to know what will happen — will they all make it? (No, Hubert says, this was the only chopper to land on this roof; those not able to get aboard waited for hours in vain.)

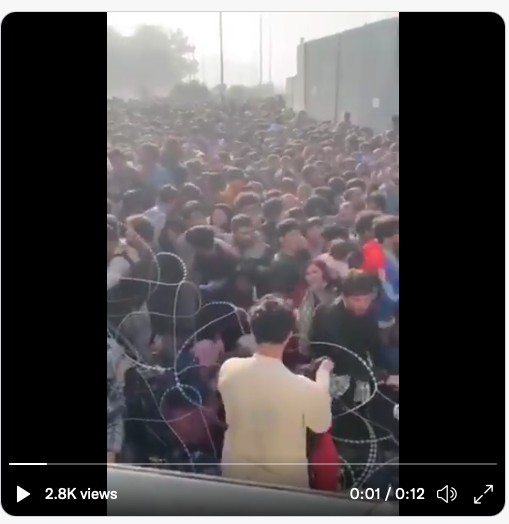

In the chaos that was Kabul Airport, 2021, it was ordinary Afghans shooting video, sometimes shortly before their own death, and that made the experience much more visceral. Part of the reason, I believe, is because the videos, like most mobile videos shot nowadays, were shot in vertical (‘portrait’) mode. (I don’t mean to demean the trauma of that situation, and what is still taking place in Afghanistan. I hope I can show that the format of such videos have helped shock us out of our torpor and, hopefully, made us empathise more with the many who either failed in their bids to leave, or died doing so.)

I was watching the key day unfold in real time on Twitter, so many of the videos lacked context, made me feel nauseous at the tragedy unfolding, and the inevitable deaths that would result. All of these moments were shot in portrait mode (I’m not going to be able to cite the sources of these videos, I’m afraid, but if anyone knows who to credit please let me know).

This first video was of young men chasing, and some clinging, to a C-17 as it gathered speed on the runway. One video, extraordinarily, was shot by one of the young men:

From another angle, back on the runway, shot by someone who didn’t make it or didn’t try, we look at the airplane gaining height:

Then another video, minutes later, shot from possibly the airport perimeter, shows the C-17 rising into blue sky, apparently an image of safety, of rescue:

Until we look closer, and realise that there are one, two specks falling from the airplane, and we realise they are the young men we had seen moments before.

For me these are the images that I will never forget, not least because they were shot by participants in the tragedy, a fumbled few seconds of footage, human beings drawn to document what they saw and what they were going through.

Then there’s the other iconic image, one perhaps more akin to Hubert’s Saigon picture: The distance shot of a C-17 making the necessarily steep climb out of Kabul:

This image is in some ways more memorable, more iconic. But I noticed that The New Yorker’s João Fazenda had chosen to recreate the image in a more vertical format, emphasising the incline of the plane, and what it had left behind:

I dwell on this because I’ve been exploring why most of us now so readily embrace vertically shot video, which, let’s face it, is lousy to watch except on a phone. But this isn’t 2012 anymore, when a faux public service video begging people not to record video in vertical format went viral. Since then we’ve, if not embraced the format, at least got used to it.

In fact, there’s an interesting body of academic and artistic work exploring the rise of vertical. Vertical Cinema as a genre had its own first premiere back in 2013 and has since had festivals and showings most years since. National Geographic released the final episode of its “One Strange Rock” documentary in 2018 in vertical format for Instagram (NatGeo has 183 million followers on Instagram and releases regular vertical versions of its programs.)

The literature points to the somewhat narrow way we look at what is an acceptable format. The reason we are used to landscape/horizontal/postbox views is because, back in 1930 the U.S. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science got together to create a standardised horizontal frame for showing in cinemas. The only ratios under consideration were 4:3, 4:5 and 4:6, and they rebuffed an argument put forward by Sergei Eisenstein, a Russian film-maker, to consider a square so as not to ignore the cinematic and creative potential of height as well as width. Instead they were more interested in making money, and a flatter, wider format suited the cinemas, theatres and dance halls of the day, where movies would be shown. So they agreed to keep the 4:3 format that most silent films had adopted. 1

There were two significant outcomes from this: the first was that henceforth the only discussion about extending the format was about width — think CinemaScope and Panavision in the 1950s — reemphasising the dominance of horizontalism. The second was that televisions would follow suit, adopting the same proportions so they could faithfully present movies when they were shown on TV.

So it’s not surprising we should be used to the format. And there are ergonomic arguments to be made for landscape mode too; we tend to see horizontally, using our peripheral vision which extends to the sides (what is called far peripheral), less to the top and bottom.2 But there are also lots of ways that we don’t think in landscape mode: we read most books in portrait mode, we often take photos of people in portrait mode (hence its, er, name) and some of us are known for tilting our monitors to better write and edit the documents we create that run top to bottom.

But there are other arguments why the vertical revolution has some staying power — and potential. One is simply practical: People hold their phones vertically 94% of the time. As long ago as 2016 90% of iOS apps were fixed in the vertical position. And that was all before TikTok. Now everyone, including Facebook, LinkedIn and Youtube, offer a vertical mode of recording and watching videos.

What I didn’t find in the literature was much about how the vertical mode has shaped us and the way we use video. Rafe Clayton suggests that this is a ‘moving image revolution’ which is clawing back control of content from the likes of Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Madison Avenue. I don’t quite buy that. Yes, this is a user-content generated shift, but that doesn’t mean the format and medium are not, or won’t be, co-opted — as can be seen by the development of ads and content by those self-same corporate types.

But I do think something is changing, and has changed. It’s not altogether desirable, but it’s definitely noteworthy. For one thing, the vertical format has changed the nature of the relationship with our devices. When the camera is on us, the relationship is altered. When we tilt the device to record ourselves in horizontal mode, it is a deliberate act of creating something for publication, broadcast; it has a self-reporting feel to it. When we keep the device in its normal position, we are adopting a more natural pose, less obviously self-conscious; more, I would argue, confessional. We are looking at ourselves (it takes a deliberate effort to look into the camera to hold the ‘audience’s’ gaze rather than look at ourselves) so we are, effectively, looking at ourselves in a mirror, and therefore everything we do after that — speaking, singing, dancing — we are at once doing for us: dancing as if there’s no-one else around, as it were. But we also know that the video is likely to be watched by someone else. So we have found an odd place for ourselves, like the tape-recordings of old that we’d make, diary entries that are self-conscious about who may see/read them, but also, inevitably, opening up.

The clearest example that springs to mind is Jennair Gerardot, the protagonist of the excellent podcast Bad Band Thing by Barbara Schroeder. Barbara explores some of the selfie videos that Jennair made ahead of the murder-suicide that is the subject of the series, when Jennair confesses her darkest thoughts and anger — we hear but of course don’t see some of the videos, but Barbara describes Jennair as looking intently at the camera, often crying and distraught, at other times practical, even as she tries to find a way to take her own life. All of this is hidden, for the most part, from her husband, as she plans her revenge with outward calm. This intimacy with the device, as if it were a friend, pet or priest who listens silently and sympathetically, suggests a deeper relationship with the camera and our phone than we may thus far have acknowledged.

Certainly there’s no shortage of selfie narcissism on display via this medium. People like joeybtoonz catalogues this on his Youtube channel, which has more than a half million subscribers, and you can’t help but look at some of his subjects and think they could do with some psychological help. But I think that’s too glib a conclusion to draw. We wouldn’t have considered writing a diary, or recording our days into a tape recorder as necessarily narcissistic. And while the visual aspect has definitely made us extremely self-conscious about how we look, to the detriment of other aspects of our lives, the portrait-mode self-video has also allowed us to communicate more intimately with those we want to communicate with, framing us and excluding the extraneous.

Where once we would record our self-videos in landscape to emphasise where we are, now many of us tighten the focus by keeping the device upright, pulling ourselves closer to the camera and breaking down the barrier between us and the viewer. Of course that also shuts us out from those around us, but there are two sides to everything. I think what we’re really seeing is what Neal Gabler has called the “mediated self”. The idea was conjured up in 1998, before the iPhone and indeed camera phones, but the idea is that we increasingly feel things don’t happen unless we record them. As Kathleen Ryan explains in applying Gabler’s idea to vertical video, we video in portrait mode because we derive pleasure from shooting video, and the device feels more comfortable vertically, more natural. “Horizontal shooting minimizes the seductive experience.” (The use of selfie-sticks, of course, is a thesis in itself.)

Go back to those days in Kabul and to the other side of the device. While it is sometimes frustrating to watch something in vertical mode, because we lack context, it also somehow and sometimes works better, pulling us into the immediacy and intimacy of the situation, where the screen is layered rather than sliced up. Here are some other examples from that week, showing the chaos around one of the gates, where those trying to get access to the airport were crammed between wall, open sewer and road (and where a suicide bomber struck). All are screen grabs from videos either circulating online or from the excellent Australian ABC documentary on the fall of Kabul:

Somehow the vertical frame makes these videos much more affecting, as if you yourself are there, just a few inches away. And each shot, by bringing the foreground so close, and adding the background, frames the scene in a way that a horizontal shot might not — or which our eyes, used to such framing, might feel less associated with. We are forced to focus on the subject, to feel their predicament. This is how Gabriel Menotti puts it:

Even in amateur videos, the portrait orientation never seems to result from the sheer negligence of the filmmaker. On the contrary, it conveys their effort to achieve the best visual composition possible given the recording situation. As the definitive fulfillment of handheld camerawork, the vertical video expresses not a disembodied, all-seeing eye, able to conform the world to the frame, but rather expresses the embodied filmmaker, placed within the same world that is being recorded, precariously handling the camera. Thus tailored for the depicted scene, the use of the vertical format is not wrong in itself.3

I can’t disagree with that. Even in such dreadful moments — possibly because of such dreadful moments — the phone becomes a device of record, shot in vertical mode because that’s the natural way to hold the device, and because after all, the shots are ultimately all of people — friends, family, a crowd, a shoe, a woman screaming behind a gate, a Talib firing into the air, a mother clutching her baby and crouching to avoid gunfire. Between them and us are only inches. We are there with them. And above us all, only sky.

- Clayton, Rafe. “The Context of Vertical Filmmaking Literature.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, January 21, 2021, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2021.1874853. ↩

- See Ryan, Kathleen M. “Vertical Video: Rupturing the Aesthetic Paradigm.” Visual Communication 17, no. 2 (May 2018): 245–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357217736660. ↩

- Menotti, Gabriel. “Proporção ‘Errada’ de Tela.,” no. 35 (n.d.): 20. ↩