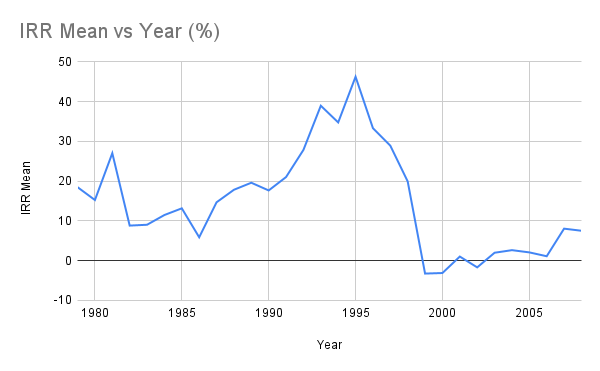

Internal rate of return on VC investment, 1980-2008 (Source: The returns of venture capital investments)

We seem to have approached a point where the existing guard has run out of ideas, and the internet community has run out of patience. I am probably wrong, but I would like to believe that the next few years will see a significant shift in the composition and direction of ‘the technology vanguard’, for want of a better term. I believe this could unleash some useful — really useful, not fake useful — innovation to drive the next generation of the web.

This is why. The most significant period in the past 25 years in tech innovation came during the dot.com winter of the early noughties. (I’ve written a bit about this before, and this blog dates back to that era.)

The half-decade after the dot.com bubble burst was one of frenetic, largely unfunded, activity that paved the way for what we now called Web 2.0 (the term wasn’t widely used until 2005) But crucially, none of this innovation perceived itself in commercial terms. There was a general feeling that the bubble of the mid- to late 1990s had very little to do with utility. Back then web companies were finding themselves flush with investment simply by putting an internet-sounding name on it.

When the bubble burst attention turned to making the web useful to individuals. Some key technologies, for want of a better word, were developed during this time. Blogging became a thing. It’s hard now for us to understand how significant this was. A blog — a web-based log — was radical in that it didn’t require any knowledge of HTML. It emphasised visually muted but appealing design — and allowed a user with no HTML or graphics knowledge to create something pleasant to the eye. And it also allowed readers to attach their comments and thoughts to the page just by typing in a box. At the time, when a website was considered static, authoritative and designed and populated by a team, this was a huge step. The first blogging platform was Pyra, set up in 1999 as a note-taking feature for project management software, by, inter alia, Ev Williams and Jack Dorsey, who later founded Twitter. Pyra had no funding and no business model: users were asked for donations.

These innovations — simplicity, writability, free — were very much the tone of the times. Others solved other problems. If lots of people were writing entries to their blogs, how could users keep up, short of visiting each blog and checking whether there were updates? Several individuals built a protocol which would create a ‘feed’ of blog posts, allowing users to ‘subscribe’ to those feeds using a piece of software called a reader. This was called RSS, standing for Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary, depending on which flavour you went for. Once again, this was all done by individuals in their spare time, probably the most notable being Dave Winer and the late and much missed Aaron Swartz. Now the content was pulled on request into one place, making the web suddenly a more productive and configurable place. When some blogs forked into audio affairs, RSS provided as easy and compelling a form of distribution for what became called podcasts as it had for blogs. RSS demonstrated the advantage of one application — the podcast app, or the blogging app — allowing itself to be integrated with other software.

Others tackled the quality of information itself. If everyone could access the internet, why shouldn’t they also be able to access the shared wisdom of everyone on it? The idea of a webpage that could be edited by anyone without even registering seemed absurd from a top-down view point, but appeared even more absurd when the goal was to build a website that aimed to be an encyclopaedia. Wikipedia, in the end, turned out to work extremely well, and still does, because of, rather than in spite of, those absurdities. Once again, the technology was developed, not for monetary gain, but because someone wanted to make something useful.

I could go on. Del.icio.us was built in 2003, a simple social bookmark-sharing service that allowed users to add tags to their entries. There was no rule about what tags you could use and what you couldn’t, nor about how many tags you added. This itself was a huge leap — del.icio.us was the first web service that took this approach, and while it may seem silly now, back then it was a major departure from the ‘rule-based’ world of hierarchical labelling and categorisation.

If all these innovations seem underwhelming it’s because they form the bedrock of our digital world now. Facebook, Twitter and nearly every social media platform owes its design, functionality and distribution to these early 2000s technologies. The key difference is that the innovations of the first half of the 2000s were rarely funded by VCs. Indeed at that time VC was in the doldrums (see chart.) Most of the tools were written on the fly, open-sourced, and discussed in pragmatic terms with only a nod to any ideological belief (usually one built around ease of use and lack of paywall) and none to the idea of any big pay-day.

I have to say as a journalist this was a really interesting time, and I believe it was central to bringing millions of people online. Blogging, far from a nerdy affair, caught the imagination of many, providing an easy way to log and share one’s interests, whether it be bee-keeping or hiking up volcanoes. Suddenly tech became useful, helpful, simple, embracing, accessible. The most interesting stuff was built by those who escaped the bust with enough money not to care, or none at all. Both spent a lot of time asking basic questions of the net and tech more broadly.

I think we’re in a similar situation now with the web, whatever you want to call it — not necessarily because the money may dry up, but because the whole thing has run out of steam. What are we doing now, exactly? What can we get excited about online? It seems to me we’re in serious trouble if we’re relying on Mark Zuckerberg to come up with a new idea and pivot Facebook in that direction. Success is as likely as Google’s forlorn attempts to reinvent itself as something other than an ad platform. These are both advertising platforms trying to find compelling reasons for users to use their services. (81% of Alphabet’s revenue in Q4 FY 2021 was from ads. So far in 2022 97.6% of Meta’s revenue has come from ads.)

The chances are slim that a successful company which invented an industry can use its money to invent a new one. Apple, I guess, is the only real example of that, and even then each new industry they create or permeate depends hugely on the success of their existing ones. There’s little point in selling services and apps if you’re not also selling the hardware they’re being distributed on.

So where might the new ideas come from? For now we’re still too interested in the technologies, not the use and users of them. All the technologies of the early noughties — blogging, RSS, tagging, wikis — arose out of frustrations with what was on offer. None had a business model or an exit strategy in mind. At present I don’t see anything really similar happening. None of us seems to be asking the question: what are we frustrated with now that could be solved by better technology? Or perhaps more specifically — how could existing technologies be built up on or re-thought to make them more useful to as many users as possible?

These are not necessarily simple questions. Partly the net is the victim of its own success. When I was writing about technology in the noughties, my main concern was to demystify technology, to make it accessible and less frightening. Now almost the opposite is required: the net has morphed from a fairly egalitarian, self-policed environment to one that is heavily controlled and directed towards extracting as much from the user as possible, be it directly or indirectly. That monetisation is largely built on the shoulder of the pioneers of the early 2000s. And so it’s unsurprising that the only real innovations Big Tech is interested in now is trying to build extra, new business models and industries atop its own dominance.

So, instead of looking for how technology can be tweaked for greater individual utility and satisfaction, we’re just looking at what technologies can be harnessed to replicate the conjuring trick that Google, Facebook and others managed before: to convert a function (search, school yearbooks) into something that can be monetised. So we see lots of interfaces for the same service — Google Glasses, Meta’s VR Metaverse. This is the old-fashioned hammer looking fora. nail.

So is there anything else? A few folk would point to blockchain as a valid and successful technology (through Bitcoin) which really was built to solve a problem we have — transferring value without having to submit to an intermediary. But that is both a blessing and a curse: Both the ICO era and the more recent DeFi era have shown that when there is a financial use case for a technology it will likely be diverted into opportunities for plunder. Those who understand it better than most will develop products that are essentially grifts, in that those who understand them better will make money at the expense of those who understand them less. That’s not to say there are some promising uses of blockchain, and the DeFi infrastructure built atop them, but they need to be developed by people not all looking for a big and quick payday, rug pull or otherwise. This crypto winter may provide some breathing space for them to do so. (Please see my declaration of interest at the bottom of this post).

And so here’s the rub: Silicon Valley is in the way here, just as their absence during 2000-2004 really helped some good ideas thrive and take flight, even if many of them ultimately ended up being bought by Big Tech and lost in a cupboard somewhere. We learned back then that a good idea doesn’t need a lot of funding; it needs a handful of smart people uninterested in an exit. I do see a few of these people, including in DeFi. At some point it may be healthier and more productive to lower one’s sights — to stop thinking that they need to build a new financial system. A new financing system, perhaps, but just solving some of the problems ordinary users face, without it necessarily changing the world. RSS didn’t save the world, but there’s a lot we wouldn’t have now if it didn’t exist.

—

Declaration of interests: I consult for a PR agency, YAP Global, which focuses on crypto, web3 and DeFi clients, and I have in the past consulted directly or indirectly for Facebook, Google, and some other tech companies on issues related to this subject. I hold some crypto assets. Thanks to Gina Chua for ideas.

Pingback: GPT: Where are we in the food chain? – the loose wire blog