Drones are changing the way wars are fought, but they’re also changing the way we experience those wars.

Television brought the brutality of war into the comfort of the living room. Vietnam was lost in the living rooms of America — not on the battlefields of Vietnam. — Marshall McLuhan (1975)

Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar is sitting injured in a what was once a red armchair in a bombed out house in Gaza, his face covered with a scarf, when an Israeli drone tracks him down. As it hovers a few feet from it he throws a stick at it, apparently knowing his fate. Tank shells and missiles rained down on the building, killing him.

A Ukrainian drone weaves between blast-shredded trees in the Kreminna forest until it finds a target: a single Russian soldier hiding in a bunker beneath a tree. He stares at the drone a few feet away and tries to fire his weapon, but it’s too late. The video turns to static, signifying the drone has exploded. (Source: GWAR69)

There’s something deeply unsettling when a war doesn’t just come to your living room, but when it makes you, the viewer, the angel of death. You are the payload, looking into the eyes of those about to be destroyed.

We are used to these videos now, either cheering along with them, or, more likely, skipping past them. The juxtaposition of technology and the banal horrors of the battlefield is nothing new, but staring into the low-res eyes of the condemned takes a bit of getting used to.

The war in Ukraine has helped gamify warfare for the civilian as for the drone operator, feeding us recordings of “first-person view” (FPV) drone attacks on vehicles, civilians, buildings and trenches — clips usually accompanied by martial music and cheering from the operators.

In some ways it’s the logical conclusion of the consumerisation of IT. First it was the office, where we brought our iPads and demanded they work with our office computers. Now it’s the battlefield, where consumer drones are pimped into service, giving us a FPV of combatants as they are hunted down in buildings, in bunkers, in fields, in vehicles. The medium, in Marshal McLuhan’s words, is the message: such videos are intuitive to us because they are no different to a first-person shooter game. The only quirk is that when the drone finds its target, the feed is lost and our imagination fills in the blanks.

Fog

It’s hard to overstate the impact of drone innovation on the way wars are being fought — and will be fought in the future — and to recognise that this is being driven not by the military industrial complex but by small, quasi-entrepreneurial teams using existing drones, 3D-plastic and -wood printers, cheap Raspberry Pi computers etc. Yes, it’s still a war of heavy artillery, jet fighters and tanks, but drones have forced their way into nearly every facet of the battlefield, to the point where commanders cannot afford to operate without them. South Korea has begun replacing mortar teams with drone teams, and former Google chief Eric Schmidt has said the US should replace its tanks with drones.

Perhaps the greatest is in the way it has not just lifted some of the fog of war, but made both intelligence and targeting highly bespoke: a soldier in the battlefield can no longer count on camouflage, the protection of steel or concrete, or even speed, to evade the enemy.

We’ve grown used to the trope in popular culture: the all-seeing eye, despatched to track down a protagonist, in Oblivion, His Dark Materials, War of the Worlds (2005), Dune etc. But few writers envisaged the reach and scale of what is being reported from Ukraine (and of course, we have to factor in that most sources have a bias, even those translating reports from Russian Telegram channels. Everyone has a dog in this fight.) Nevertheless, there’s little doubt that in the nearly three years since the Russian invasion of Ukraine beyond those parts annexed in 2014, no other weapon has evolved so quickly.

Drones patrol the sky hunting for prey. Any soldier is a potential target for a kamikaze drone. A Russian soldier walking to a nearby village for spare parts is killed on his way back to his mortar battery. His platoon commander and a fellow crewman are spotted; the latter is killed, the former loses a leg. (Source: WarTranslated)

Soldiers have grown used to surrendering to drones — what is called “non-contact surrender”, according to David Hambling, writing in Forbes. In one image shared online, what appears to be a Russian soldier attempts to surrender to a drone, holding up a piece of equipment as a bargaining chip. The equipment is likely a relatively basic Russian-made drone jammer.

Russian soldiers have reported that they have been threatened with attack from their own drones if they do not comply with orders to advance. “If you don’t want to go, they throw a grenade from above to speed you up,” the soldier, Lt Oleg Guivik, is quoted as saying by military researcher Chris O, who translated text and a video found on a Russian Telegram channel. (It’s not possible to verify the source material.)

Substitute robot for drone and you can see how far we have come, and where all is this going.

Indeed the tail has begun to wag the dog. Social media teams embedded in units quickly edit and circulate FPV videos. Their popularity has allegedly inspired Russian commanders to co-opt the drones for filming propaganda for their superiors rather than for military purposes, according to one Telegram channel.

Battle-ground

The result is that drones factor in to many battlefield decisions. Artillery weapons fired less than 20 km behind the front line, says Trent Telenko, a specialist in military logistics, can’t relocate fast enough to avoid drone counter-fire. Evacuation of the wounded and civilians is vastly complicated by the threat of drones, according to a piece by Kris Parker in Byline Times, even when the evacuation is done by civilian volunteers.

Although Putin has taken the trend seriously — last year he said Russia aimed to increase its supply of drones by a factor of 10 this year, to 1.4 million. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said it can produce 4 million drones a year, according to Parker. The numbers are probably meaningless, for several reasons. Many drones are either bought by the units themselves, or donated. Some never appear: Russian front line troops have complained that commanders take donated drones and sell them at local markets.

Barbecue

What is clear is that the evolution of drone warfare will continue to be rapid. It is a war of attrition, where each tries to parry the other’s technological thrust.

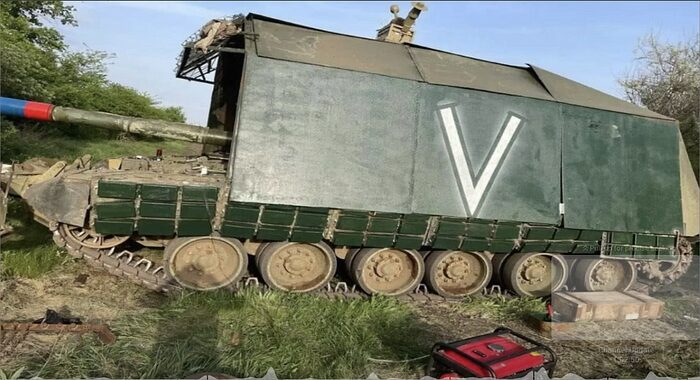

Russian soldiers have done their best to protect themselves and their vehicles from drones, with limited effect. They have constructed wire cages atop their tanks, called ‘cope cages’ by some, though their effectiveness is unclear, given the Russians prefer to call them ‘barbecues’, and their larger, turtle-like shell, a ‘king barbecue’, suggesting they don’t have much faith in them. Indeed Ukrainian munition producer Shock Wave Dynamics has recently produced a 3D-printed bomb that punches debris in a specific direction, nullifying any cage or shell, according to Stuart Rumble of BFBS Forces News.

Others simply hope to outrun the drones on motorbikes.

Jamming the signal between drone and operator is still the most effective defence. Beyond jamming, both sides have been experimenting with net launchers, which are released to ‘capture’ the target drone and bring it down. FPV drones have been successful in intercepting long-range fix-winged drones like the Russian Gerbera, usually by crashing into them kamikaze-style. Other approaches include trying to nudge it off course.

In response to jammers, Russians started using fiber-optic cable drones, using a spooling line of angel-hair thin cable to control the drone and feed back high definition video until it reaches its target. While the fibre optic cable reduces some its manoeuvrability, it renders useless drone jammers which rely on intercepting wireless signals between drone and operator.

Autonomy

It is inevitable that drones both large and small will become more autonomous, free of the need to be directed by a remote operator, able to find the target itself, and therefore be invulnerable to jamming of communications or GPS signal. In other words, a seeing drone able to make its own decisions.

Max Hunder of Reuters wrote in July that Ukrainians are already working on this, looking to create a targeting system that is cheap and easy to build, using Raspberry Pi computers and a simple program. Indeed, this is where the next breakthroughs are likely to come. The cost of making drones is falling, but thousands of them are expended each week. The goal will have to be to make drones that can not only evade defences but deliver a punch worth the effort.

So expect to see more like Kyiv-based Swarmer, a startup which is using AI to automate the launching and flight of fleets of drones, according to a Hunder. Possibly helping such initiatives will be that they are less dependent on government budgets and more on private money, especially Silicon Valley’s. Swarmer just finished a round that included not just a defence tech company (R-G.AI) but also a Web3 player, an LA-based VC focused on Ukrainian startups and aerospace-focused VC Radius Capital Ventures.

AI is already being used to direct some of the country’s long-range drone strikes inside Russia, Hunder wrote, quoting an unnamed official as saying that such attacks sometimes involve a swarm of about 20 drones, in part to divide up tasks and to distract and confuse defences.

What is clear is that the lines between a military drone and a consumer drone are blurring. At the beginning of the war drones could drop little more than a hand grenade. Now Ukraine’s “Baba Yaga” drones can carry a 40 kg bomb, according to Daniel R, an imaging physicist, citing photos from Ukrainian X feed @watarobi. (Much of the bomb and release appear to have been 3D-printed.)

Ukraine’s thermite “Dragon” drones appeared in late August, one dropping molten metal as it sped along a tree-line, setting trees and undergrowth ablaze in a display frighteningly reminiscent of napalm raining down on Indochina. Thermite is a combination of oxidised iron and aluminium that burns at about 4,440° F (2,448.89° C), according to Howard Altman of The War Zone, effectively making it a sort of modern-day flamethrower, dropped or sprayed. They are now being used on tanks and bunkers, small enough to navigate their way through narrow slits that were previously considered impenetrable.

So what does all this mean?

I’d offer a few thoughts.

Assassins

From a tech point of view, we’re seeing drones, 3D printing and a startup mentality (and VC funding) all find their natural fit: dual-use. AI is on the way to doing something similar: ex-Google CEO Schmidt, has been working on AI-driven military drones with a startup he founded, White Stork. As I mentioned above, he has called on the US to ditch its tanks, and in a speech in Saudi Arabia last month, predicted that artillery would also disappear. He called drone warfare “the future of conflict” driven by the rapid decline in the “cost of autonomy.”

He’s got stuff to sell, so of course he would say that. But there’s no denying a revolution has taken place without us really noticing. We have entered the era of robot warfare, but not as we envisaged it. We expected humanoid droids of some kind, but instead we are getting consumer quadcopters strapped together with duct tape, bombs and their hardpoints 3D-printed from plastic or wood, granted intelligence by an off-the-shelf computer the size of a small stack of credit cards. Cost: about $150, compared to a military drone costing between $60,000 and $25 million.

Think of them as small, fast, roving assassins, for now. The next step is swarms of robot drones each with a slightly different task, operating, as Schmidt predicts, autonomously.

All of this will be, is being, captured on video, and beamed onto your phone, should you wish to see it.