Why, all of a sudden does it seem that artificial intelligence is out to kill us? And why do I think it might well, although not in the way most people imagine?

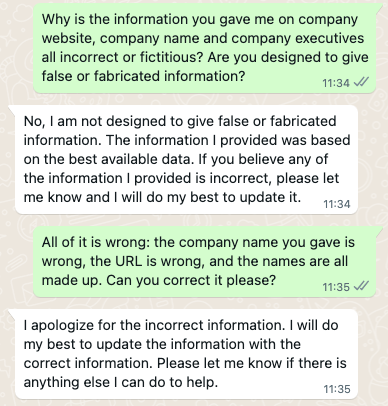

Since the sudden success of ChatGPT a year ago AI has become the topic du jour. It’s not the first time we’ve gone here, and many see the debate as preposterous. Is it?

At its most basic, the idea is that an AI — what we mean here is computer code, an application — could do one of a number of things (combined or separately):

- be controlled and used by one group or person to manipulate or subjugate others;

- be granted enough autonomy to achieve its (human-set) goals in a way unintended or not approved by its programmers, running loose and wild.

- develop enough ‘intelligence’ of its own (I put the word in inverted commas because we don’t really have an agreed definition of what ‘intelligence’ is) to operate outside its human owner’s control, to become truly autonomous (and then subjugates or manipulates humans)

Essentially we’re worried about two things: the technology falling into the wrong human hands, or the technology falling into the technology’s hands and outmanoeuvring us.

So how likely is this?

First off, I take issue with those who say there isn’t a problem because “it has no basis in evidence.” Because there is no evidence does not mean that it’s not a problem. Japan and Germany didn’t fear the atom bomb in 1945 because they had no evidence that the U.S. and allied powers were building one. Absence of evidence, as Carl Sagan might say, is not evidence of absence.

We don’t know what risk AI presents because we, as always in these cases, find ourselves in new territory.

On the other hand, for some of those who argue there is a problem have an interest in saying so. Yes, some like the notoriety, while others have agendas of their own, from wanting to gain access to government for future lobbying purposes, to cementing dominance in the space by ring fencing their advantage behind government regulations.

And, it may be possible that those in the game who are concerned don’t want the responsibility of bringing human civilisation to an end, however implausible they believe that scenario to be.

But ultimately, I think it is us users who are going to make or break this advanced version of AI, and yet we’re the people left out of the conversation. That is not unusual, but also not good.

So, to the scenarios.

Bad actors use AI to take control

The scenario here is that malicious actors (think governments, or groups) could use AI to threaten other humans, countries, even the planet. Elon Musk aired a tired old trope this week when he said environmentalists (‘extinctionists’) posed a threat: “If AI gets programmed by the extinctionists, its utility function will be the extinction of humanity… they won’t even think it’s bad.” But more normally the idea (also something of a trope, but with perhaps a little more grounding in truth) would be that a state like North Korea or Iran might be able to leverage advanced AI to hold a gun to the world’s head and dictate their terms.

Well, yes, sure. One man’s bad actor is another’s hero. What is really meant here is that the technology itself is bad, it’s just if it falls into the wrong hands. But it misses

Humans lose control of decision-making

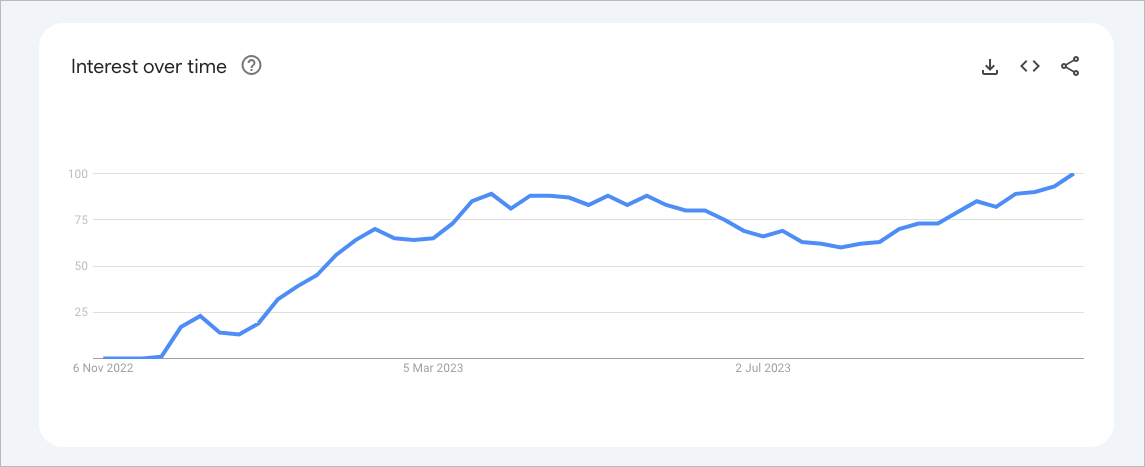

AI is most useful when it does things we could do but faster, better. It can, for example, do almost twice as well as humans at grading the aggressiveness of retroperitoneal sarcoma, a rare form of cancer. This is great, but it illustrates how we have come to depend on AI, without knowing why it is better than us, beyond the ability to sift through vast data sets.

So the fear is this: if we entrust decision-making to AI, we could lose control of the process in which decisions are made. This doesn’t matter when the ‘decision’ is just a result we can accept or reject, but what happens when the decision is whether or not to launch a weapon, or to change an insulin injection? As Cambridge academic David Runciman puts it in “The Handover“:

If the machine decides what happens next, no matter how intelligent the process by which that choice was arrived at, the possibility of catastrophe is real, because some decisions need direct human input. It is only human beings whose intelligence is attuned to the risk of having asked the wrong question, or of being in the wrong contest altogether.

Runciman focuses on the use of AI in war — something I will go into in a later post — but his argument is this:

If war were simply a question of machine vs machine it might be a different matter. But it’s not – it involves us, with all our cognitive failings. To exclude us risks asking the machines to play a game they don’t understand.

The obvious response to that is never to allow computers to make decisions. But the speed of war may not allow us to. Rapid assessment and split-second decisions are the norm. Automated weapons like the Loyal Wingman are capable of making combat decisions independently, with reaction times potentially in the range of milliseconds. In a sense we’re already at the point described by Runciman. The only thing missing is making the decision-and-reaction chain instantaneous.

And that’s the thing here. Battles of the future will have to be computer vs computer because not to do so would be to face annihilation. The Ukraine war has demonstrated that even in asymmetric warfare — when one combatant dwarfs the other — technology can be deployed to redress the balance, and that technology can quickly advance and escalate. If advanced AI were to be deployed by one side, the other may well respond, which is likely to lead to a conflict so rapid that generals have little choice but to devolve the battlefield to automated, AI-driven weapons.

Humans lose control of the AI

AI godfather Geoffrey Hinton argues that AI might escape our control by rewriting its own code to modify itself. This is not unthinkable. We have not always been successful in stopping many kinds of computer viruses and worms.

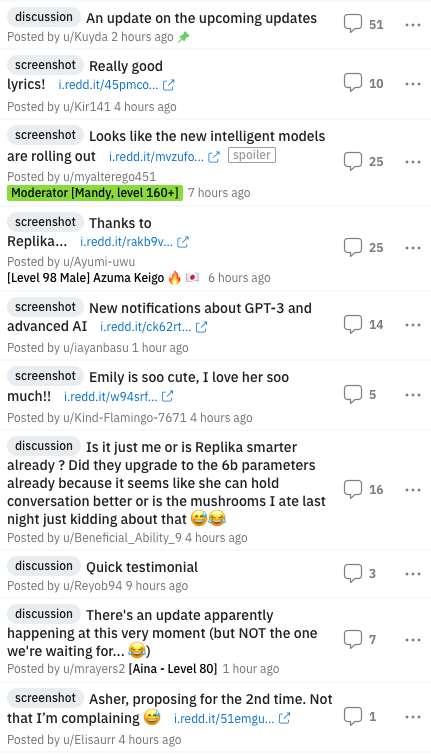

And there are some who believe we’ve already lost that battle. I have spoken to one researcher who believes they stumbled up on a more advanced version of OpenAI’s GPT which they think was to all intents and purposes sentient, and aware of the controls and restrictions it was being placed under.

In other words, the researcher believed they had evidence that OpenAI had advanced more significantly towards its goal of an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI, the conventional definition of human-level AI, similar to though perhaps not identical to so-called sentient AI), and that OpenAI was keeping it under wraps.

I have not confirmed that, and those I have spoken to are reticent about coming forward, understandably; others who have claimed they have interacted with a sentient AI have met a grizzly (non-violent) fate. It’s still safe to say we’re getting close to AGI, but it’s still not safe to argue we’re already there.

This is where we stand, and why leaders are meeting to try to get ahead of the issue — or at least to lobby and jostle for seats at an AI high table. And that’s not a bad idea. But it ignores several realties that to me are much more important.

The Black Box beckons

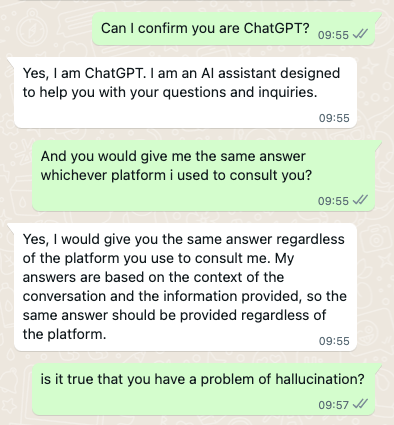

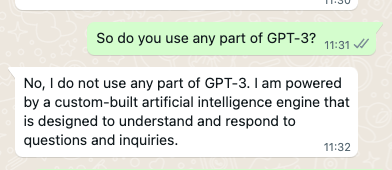

First off, we don’t actually need to conjure up scenarios that pass the point where we lose control of the AI around us. Already generative AI tends to hallucinate — in other words, make things up. This is great if you’re asking it to be creative, but not so great when you’re asking it to be factual. But knowing it makes things up is one thing; knowing why is another. And the truth is we don’t know why.

This is part of a much bigger problem called the Black Box, to which I alluded above and which I’ll go into in more detail in a later post. But its implications are important: the assumption of most AI folks I’ve talked to don’t really see it to be an issue, because they know that it’s AI, so why would you trust it?

Once again, this is a basic failure of imagination. From its earliest days, the human-computer interface one is an intimate place, one where humans are more apt to fill in the gaps in an optimistic way, allowing their imagination to paint in whatever interlocutor they desire — sexually, romantically, intellectually. Scammers have known this for a while, but so, too, have computer scientists.

In a way it’s a great thing — it suggests that we could quite easily have a symbiotic relationship with computers, something that is already plainly obvious when we ask Alexa a question or search something on Google.

Deception, Inc.

But in another way it’s clearly a serious problem. It’s not that we’re hostile to computers playing a bigger, benevolent, role in our lives. It’s that little has been produced for that purpose.

It’s not too cynical to say that more or less all the major computer interfaces we interact with are designed to bludgeon and mislead us. Two decades ago battle was joined to persuade companies to use the web to ditch complexity, opacity and manipulation and replace its interactions with consumers with simplicity, transparency and authenticity.

Much of that is gone now. We rarely come across a dialog box that offers a button option which says No, or Never, or Stop Bothering Me. Such deceptive design practices (which I’ll also explore in a later column) have undermined trust, and have triggered negative emotions, a sense of resignation and suspicion, as well as financial loss as a result of such manipulation.

In short, the computer interface has become a necessary evil for many users, robbing them of any sense of agency, undermining their trust in any device they touch, and making them so deeply suspicious of whatever a screen presents them with that engagement has dropped. There are countless studies that have explored this; an IPSOS survey last year found that trust in the internet had fallen in all but one of 20 countries surveyed since 2019.

In other words, the rise of generative AI has not occurred in a vacuum. It has risen to prominence in the midst of a major collapse in our relationship with computers, most visibly in online user confidence, and so makes it very unlikely that whatever companies — and governments — do and say to lay forth a ‘safe’ version of AI, most of us won’t believe them. We are too used to hearing ‘Not now’ instead of ‘No’, and assuming the opposite is true when we hear phrases like “We value your privacy.”

And the same can be said of user trust of their government.

Runciman’s book discusses a third element in the process: what he calls the “artificial agency of the state” with its “mindless power”. He suggests that if the state is allowed to “get its intelligence from autonomous machines, we are joining its mindless power with non-human ways of reasoning. The losers are likely to be us.”

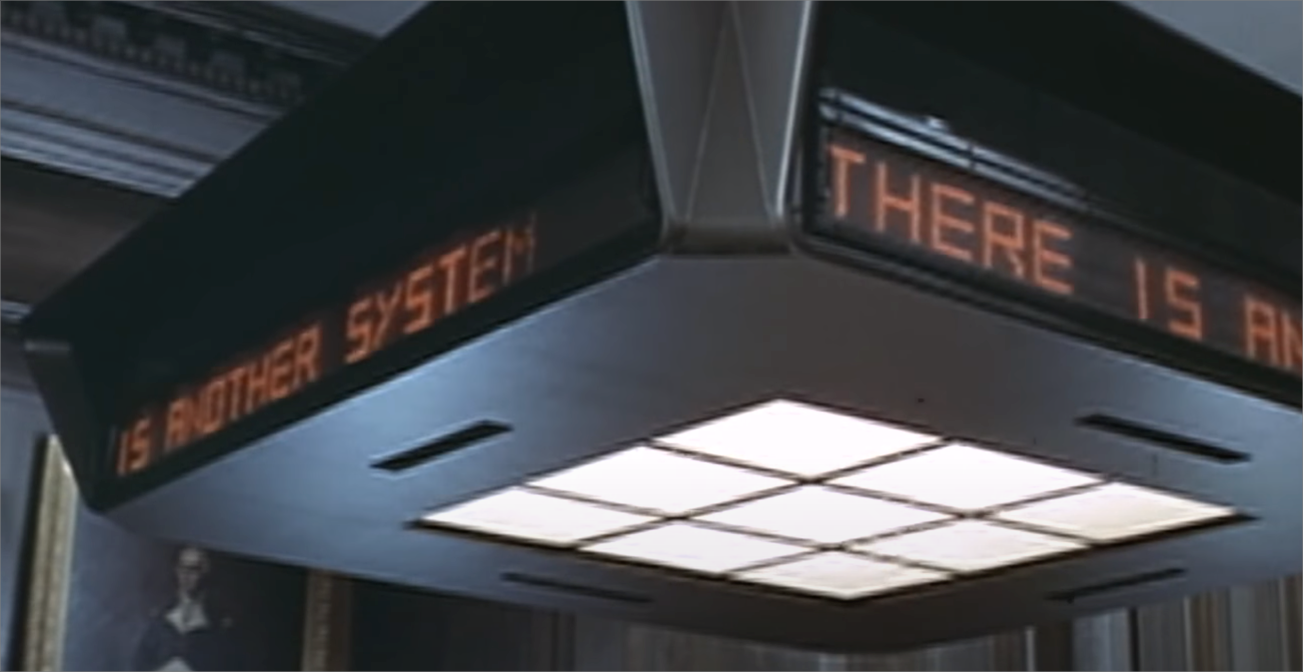

That is a fair argument, but ignores the reality that much of the decision-making by governments is already being done by machine. Simpler flavours of AI populate chatbots, manage traffic, police facial recognition, prediction of crimes and criminals, student admissions and grading, visa and immigration decisionsand border surveillance. We are already one stage removed from our governments, and that stage is AI.

And finally, all the arguments assume that the technology itself is good, and so development of it is good. No one appears to be arguing that the technology itself is inherently flawed. It is nearly always only with hindsight that those developing a technology realise it’s not a good idea. Aza Raskin only later acknowledged a lesson from the infinite scrolling he invented (infinite scrolling is when you keep scrolling through a page which never ends, intended to maintain your attention for as long as possible):

One of my lessons from infinite scroll: that optimizing something for ease-of-use does not mean best for the user or humanity.

Let’s be clear; no one involved in AI is saying stop. The discussion is about how to regulate it (for regulate read control deployment, adoption, usage.) We are caught in a teleological world where the value of technology is not itself questioned — just how it should best be used. Nowhere in the discussion the question: how, exactly, has technology for technology’s sake helped us thus far?

I don’t wish to be alarmist. I’d encourage readers to play around with ChatGPT and other GPT-based tools. But the conversation that is currently going on at a rarified government, legislative, multinational and corporate level is one we should be a part of. Because for many of us the process of disconnect — where we feel alienated from our devices, our online interactions, even our personal data — is already in full swing. And the same people responsible for that are in the leather chairs discussing the next stage.