We’re living in a digitally ass backwards age, where everything you do of commercial monetary value is retained, amazingly easy to recover and commercially mined at mind-boggling speed, but everything else — photos, an SMS, an email you sent to someone last week, the deed to your house — is lost in the muddle of that drive an inch or two from your finger tips.

Mike Bird’s tweet above is one illustration of this paradox. But perhaps the best one is this: I have a vast database of stuff I’ve collected over the years from the internet. But although I use the best tools out there to index that stuff, it’s still much easier to search for those documents on the internet via Google. Easier as in faster and more thorough (more documents, newer versions). It wasn’t always so, however. For one thing, the internet wasn’t always faster than your apps+your hard drive.

For another, Google used to have an excellent tool called Google Desktop which searched your computer for you while also searching the net. This was during the wonder years of 2004 through to about 2008 when software was Good, in both senses of the word, and the idea of indexing your hard drive and making things easy to find seemed like a worthy cause; some of you may recall Enfish and some other efforts in this field, which I suspect Google Desktop killed off before it took its own life, probably having completed its mission.) For a heavenly few years the two were united: what you had in your computer and what was online were one and the same.

But Mammon won. Because the simple calculation was: there is no commercial value on your hard drive because privacy prevents Google from mining that data or learning intent from your searches so why would we waste money on that. Once Google had won the search engine wars in the 2000s (see my post on that here) which was what the Google Desktop war was about, Microsoft being their main competitor at the time), there was simply no commercial imperative in continuing to support Google Desktop. Besides, by then we had been persuaded to move most of our email onto the web, so why would we want to be searching our hard drives anyway? There really is no market for what I, foolishly, once believed was the future of the browser. To me then, and now, I still can’t quite figure out why would you NOT search the web and search your own computer at the same time?)

So in short: search is only valuable to the provider of that search if it is to look for things of commercial value, and things we have not yet purchased, and things we might intend to purchase, and have the means of purchasing. It’s not hard, when you look at it that way, to see how things have skewed, in the past 20 years from a paradigm of: “Your computer! It will be where you will create and save all your memories, your documents, your house plans, your photos, all in one place! Forever!” To: “Your devices! You can consume anything you like! Whenever you like! Instantly! Forget about the future! Live for now!”

OK, that’s obvious for the ‘order now from the gig economy’ world. But it started long ago. It started with iTunes, and continued with things like Kindle. Those digital books you ‘bought’? You don’t own them. You bought a license. You die, that book reverts to Amazon. You might be able to save those items somewhere, but you can’t really do anything to them as if they were yours, you can’t search them outside the Kindle app. They are imprisoned.

And yes, it’s true that your photos are saved from your camera relatively seamlessly to other devices, except it’s less than obvious how, evidenced by all the hours you spend trying to find a photo from that birthday party ten years ago that should have been saved to a computer but doesn’t seem to have been because that computer was upgraded a few years ago and doesn’t seem to have been moved across, or the WhatsApp message that was on an old phone or an email that was on an old account which you ditched when they started charging outrageous fees for attachments. Or automatic online and time machine backups which all go smoothly for years until you actually need to restore something in which case the one file you need is missing. And did you know that hard drives actually only last five years tops? Assuming you’ve been using hard drives to back up your treasured memories for 15 years (20 in mine) that means you should have replaced those hard drives at least twice.

In short, even if you have been doing everything right, you’ve been doing it wrong.

Our digital world is built to be commercially optimised for speed, not for ensuring our memories, our records, our heirlooms, belong to us, and are safe. This is not to say companies like Apple don’t try to sell us the whole shebang, make us feel that by selling us computer+services+software that we’re still in that 20-year-old paradigm of ‘your own computer where only good things happen’ but in fact it’s better to think of it as as a big shopping cart. Few of the things you do with it you actually create or produce, and while Apple does offer some tools to help you move stuff from one old device to another, the emphasis is not on safeguarding your ‘digital heritage’ as much as persuading you to keep subscribing to their digital services — to expand your plot in their walled garden.

Now you could argue, I suppose, that Facebook has taken a different approach, building a business on digital longevity, lovingly creating a website that thrives on us tending to our shared memories. And perhaps there’s some truth in that. But let’s explore that for a moment. Can I easily search my memories for something? Sort of. I suppose if I organised things correctly I could find a birthday party album. But the search bar on the timeline doesn’t seem to work, and the best way to navigate seems to be by year. That is a tedious option. Overall, the Past in Facebook world seems to be something for the company’s algorithms to dish up occasionally, rather than a place for us to explore. Like Google, Facebook presumably has less interest in it because it’s not reflective of our present or upcoming needs and desires.

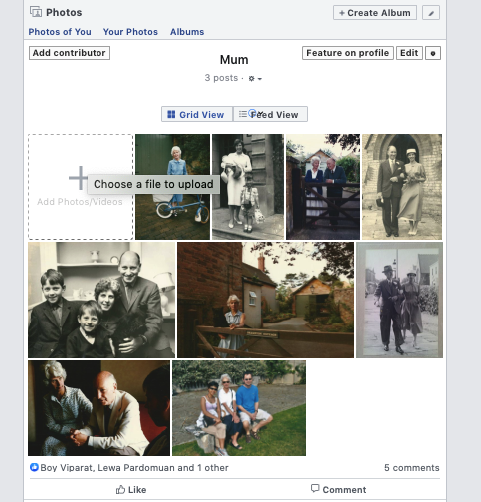

It’s time for us to apply some pressure for the commercial world to stop thinking like this. We have given so much of our lives and data to these vast harvesting machines it’s time to wrest some of it back. And not just to demand the data, but to demand it in the format that we left it in. For example: You can now download your data from Facebook and Google but this is all — intentionally, in my view — in such a mess that it would take a year to put it some order. It is absurd, in my opinion, that the tools to curate our footprint online are impressive (in Facebook, for example, I can create an album called ‘Mum’ to remember my mother, where the photos are dated, geotagged and name-tagged, where they are displayed as thumb-nails and where I can choose who can view them and where those people can comment. This is all assumed as based features.

Now if I want to download that album to my computer, how do I do that? It took me one minute (not too bad, considering) to figure out that (arguably) probably my best option was to download all my photos. This of course may take some time. So while that was going on I decided to right click and download the photos individually. Now to be fair this is not as hard as it could be (in Safari, right click on the image, download as image to the default folder). The problem is that all that richness and effort is lost: The filenames are now meaningless — 30535610150348063416882213385n.jpg rather than 1959 Mum with baby Aldrich.jpg— the metadata is gone, the geotagging, the people tags, the comments, the albums. All that curating work you did on Facebook is for naught. It’s a stark reminder that the tagline about Facebook caring about you and your memories is a flagon of balderdash. (The download process is no better, though the albums are at least in separate folders.)

So that’s the first step. I will talk about future steps in future columns. Perhaps this Covid-19 year (and some of next, no doubt) will not be such a waste. We will realise the devices in front of us are not just oversized credit card swiping machines or pocket-sized cinemas, but actual treasure chests for organizing and storing our heritage, our heirlooms, things we can create and pass on. But first we need to reclaim them. This needn’t be a zero sum game. The Walled Garden machines can help us do this, and expand their business models to include better, more resilient home networks that include resilient storage, tagging and search (more of this in a future column.)

For now, start thinking: all this digital gardening you’re doing? Who is it for? And will it leave it a trace for anyone but those hordes of digital marketers?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download