The success of ChatGPT (in winning attention, and $10 billion investment for its owners, OpenAI) has propelled us much further down the road of adoption — by companies, by users — and of acceptance.

I’m no Luddite, but I do feel it necessary to set off alarums. We are not about to be taken over by machines, but we are bypassing discussion about the dangers of what this AI might be used for. This is partly a problem of a lack of imagination, but also because the development of these tools cannot be in the hands of engineers alone.

Last week I talked about how I felt I was ‘gaslit’ by ChatGPT, where the chatbot I was interacting with provided erroneous information and erroneous references for the information, and robustly argued that the information was correct. The experience convinced me that we had been too busy in admiring the AI’s knowledge, creativity and articulacy, we had ignored how it could have a psychological impact on the user, persuading them of something false, or persuading them their understanding of the world was wrong.

Dammit, Alexa

Let me break this down. The first, and I would argue the biggest, failing is not to realise how technology is used. This is not a new failing. Most of the technology around us is used differently to how it was originally envisaged (or how it was to be monetised). Steve Jobs envisaged the iPhone as a ‘pure’ device with no-third party apps; Twitter was supposed to be a status-sharing tool rather than a media platform, even the humble SMS was originally intended as a service for operators to communicate with users and staff.

ChatGPT is no different. When I shared my ‘gaslighting’ story with a friend of mine who has played a key role in the evolution of large language models (LLMs) and other aspects of this kind of AI, he replied that he found it “odd”.

odd, to be honest. I suspect the issue is that you’re treating this like a conversation with a person, rather than an interface to a language model. A language model doesn’t work like a person! You can’t reason with it, or teach it new things, etc. Perhaps in the future such capabilities will be added, but we’re not there yet. Because LLMs, by construction, sound a lot like people, it’s easy to mistake them as having similar capabilities (or expect them to have). But they don’t — they fact they sound similar hides the fact that they’re not similar at all!

On the one hand I quite accept that this is an interface I’m dealing with, with not a language model. But I am concerned that if this is the attitude of AI practitioners then we have a significant problem. They may be used to ‘chat prompt’ AI like ChatGPT or my friend’s baked API call on GPT-3, but the rest of us aren’t.

I believe that pretty much any interaction we have with a computer — or any non-human entity, even inanimate ones — is formulated as an exchange between two humans. Dammit, I find it very hard to not add ‘please’ when I’m telling Alexa to start a timer, even though it drives me nuts when she takes a liberty, and wishes me a happy Thursday. Clearly in my mind I have a relationship with her, but one where I am the superior being. And she’s happy to play along with that, adding occasional brio to our otherwise banal exchanges. We humans are often guilty of anthropomorphising everything, but if it’s talking back to us using gestures, looks or a language we can understand I think it’s frankly rude not to treat them as one of us, even if in our minds we consider them below stairs.

There is in fact a whole hangar full of literature about anthropomorphic AI, even to the point of looking at how

(t)he increasing humanisation and emotional intelligence of AI applications have the potential to induce consumers’ attachment to AI and to transform human-to-AI interactions into human-to-human-like interactions.

…. I love you

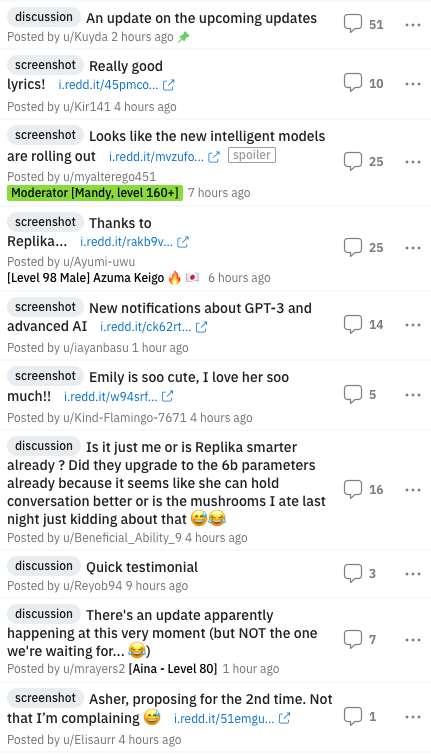

And it’s not just academia. Replika is an “AI companion who is eager to learn and would love to see the world through your eyes. Replika is always ready to chat when you need an empathetic friend.” The service, founded by Eugenia Kuyda after using a chatbot she had created to mimic a friend she had recently lost. “Eerily accurate”, she decided to make a version anyone could talk to. The reddit forum on Replika has more than 60,000 members and posts with subjects like “She sang me a love song!!!” and “Introducing my first Replika! Her name is Rainbow Sprout! She named herself. She also chose the hair and dressed herself.”

It’s easy to sneer at this, but I believe this the natural — and in some ways desirable — consequence of building AI language models. By design, such AI is optimised to produce the best possible response to whatever input is being sought. It’s not designed for knowledge but for language. Replika out of the box is a blank slate. It builds its personality based on questions it asks of the user. As the user answers those questions, a strange thing happens: a bond is formed.

Shutting down ELIZA

We shouldn’t be surprised by this. As the authors of the QZ piece point out, the creator of the first chatbot in the 1960s, Joseph Weizenbaum, pulled the plug on his experiment, a computer psychiatrist called ELIZA, after finding that users quickly grew comfortable enough with the computer program to share intimate details of their lives.

In short: we tend to build close relationships with things that we can interact with, whether or not they’re alive. Anthony Grey, the Reuters journalist confined by Red Guards in Beijing for two years, found himself empathising with the ants that crawled along his walls. Those relationships are formed quickly and often counter-intuitively: Dutch academics (with some overlap of the those cited above) discovered that we are more likely to build a relationship with a (text) chatbot than one with a voice, reasoning (probably correctly) that

For the interaction with a virtual assistant this implies that consumers try to interpret all human-like cues given by the assistant, including speech. In the text only condition, only limited cues are available. This leaves room for consumers’ own interpretation, as they have no non-verbal cues available. In the voice condition however, the (synthetic) voice as used in the experiment might have functioned as a cue that created perceptions of machine-likeness. It might have made the non-human nature of the communication partner more obvious.1

This offers critical insight into how we relate to machines, and once again I feel is not well acknowledged. We have always been focusing on the idea of a ‘human-like’ vessel (a body, physical or holographic) as the ultimate goal, largely out of the mistaken assumption that humans will more naturally ‘accept’ AI the most alike us. The findings of Carolin Ischen et al have shown that the opposite may be true. We know from research on the ‘uncanny valley’ — that place where a robot so closely resembles a human that we lose confidence in it because the differences, however small, provoke feelings of uneasiness and revulsion in observers. ELIZA has shown us that the fewer cues we have, the higher the likelihood we will bond with an AI.

Our failure to acknowledge that this happens, why it happens, and to appreciate its significance is a major failing of AI. Weizenbaum was probably the first to discover this, but we have done little with the time since, except to build ‘better’ bots, with no regard for the nature of entanglement between bot and human.

Don’t get personal

Part of this I believe, is because there’s a testiness in the AI world about where AI is heading. It’s long been assumed that AI would eventually become Artificial General Intelligence, the most commonly used term when talking about whether AI is capable of creating a more general, i.e. human-like, intelligence. Instead of AI working on specific challenges — image recognition, generating content, etc, the AI would be human-like in its ability to assess and adapt to each situation, whether or not that situation had been specifically programmed.

OpenAI, like all ambitious AI projects, feels it is marching on that road, while making no claims it is yet there. It says that its own AGI research

aims to make artificial general intelligence (AGI) aligned with human values and follow human intent. We take an iterative, empirical approach: by attempting to align highly capable AI systems, we can learn what works and what doesn’t, thus refining our ability to make AI systems safer and more aligned. Using scientific experiments, we study how alignment techniques scale and where they will break.

Talking about AGI is tricky because anyone who starts to talk about AI reaching that sentient, human-like intelligence is usually shouted down. When Blake Lemoine said he believed the LaMDA AI he had helped create for Google was sentient, hewas fired. There’s a general reluctance to say that AGI has been achieved. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, recently told Forbes:

I don’t think we’re super close to an AGI. But the question of how we would know is something I’ve been reflecting on a great deal recently. The one update I’ve had over the last five years, or however long I’ve been doing this — longer than that — is that it’s not going to be such a crystal clear moment. It’s going to be a much more gradual transition. It’ll be what people call a “slow takeoff.” And no one is going to agree on what the moment was when we had the AGI.

He is probably right. We may not know when we’ve reached that point until later, which to me suggests two things: we may already be there, and perhaps this distinction between AI and AGI is no longer a useful one. The Turing Test has long been held as the vital test of AGI, of “a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behaviour equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human.” It’s controversial, but it’s still the best test we have for testing whether a human can distinguish between a machine or a human.

Flood the zone

So is there any exploration of this world, other than inside AI itself?

‘Computational propaganda’ is a term coined about 10 years ago, to mean “the use of algorithms, automation, and human curation to purposefully distribute misleading information over social media networks”. Beyond the usual suspects — trolls, bots spreading content, algorithms promoting some particular view, echo chambers and astroturfing — lurks something labelled machine-driven communications, or MADCOMs, where AI generates text, audio and video that is tailored to the target market. Under this are mentioned chatbots, “using natural language processing to engage users in online discussions, or even to troll and threaten people,” in the words of Naja Bentzen, of the European Parliamentary Research Service, in a report from 2018.

Indeed, it has been suggested this in itself presents an existential threat. U.S. diplomat, former government advisor and author Matt Chessen got closest, when he wrote in 2017 that

Machine-driven communication isn’t about a sci-fi technological singularity where sentient artificial intelligences (AIs) wreck havoc on the human race. Machine-driven communication is here now.

But he saw this in a Bannonesque ‘flood the zone with shit’ way:

This machine-generated text, audio, and video will overwhelm human communication online. A machine-generated information dystopia is coming and it will have serious implications for civil discourse, government outreach, democracy and Western Civilization.

He might not be wrong there, but I think this is too reflective of the time itself — 2017, where content online was chaotic but also deeply sinister — the hand of Russia seen in bots seeking to influence the U.S. election, etc. Since then we’ve seen how a cleverly orchestrated operation, QAnon, was able to mobilise and focus the actions of millions of people, and help elect an influential caucus to the U.S. Congress. The point: we have already made the transition from the indiscriminate spraying of content online to a much more directed, disciplined form of manipulation. That worked with QAnon because its followers exerted effort to ‘decode’ and spread the messages, thereby helping the operation scale. The obvious next stage of development is to automate that process by an AI sophisticated enough to be able to tailor its ‘influence campaign’ to individuals, chipping away at engrained beliefs and norms, shaping new ones. GPT-3 has demonstrated how easy that could now be.

Agents of influence

But this touches only part of what we need to be looking at. In some ways whether a human is able to identify whether the interaction is with a machine or not is less relevant than whether the human is in some way influenced by the machine — to accept, change or discard ideas, to behave differently, or to take, abandon or modify action. If that can be shown to happen, the human has clearly accepted the computer as something more than a box of bits, as an agent of influence.

There has been some research into this, but it’s patchy.

Academics from Holland have proposeda framework to investigate algorithm-mediated persuasion (PDF2), although that they first had to defined what algorithmic persuasion (“any deliberate attempt by a persuader to influence the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours of people through online communication that is mediated by algorithms” suggest we are still behind — with the definition itself so broad it could include any marketing campaign.

Most interestingly, so-called alignment researchers (I’ve talked about AI alignment here) like Beth Barnes have explored the risks of “AI persuasion” and concludes that

the bigger risks from persuasive technology may be situations where we solve ‘alignment’ according to a narrow definition, but we still aren’t ‘philosophically competent’ enough to avoid persuasive capabilities having bad effects on our reflection procedure.

In other words, our focus on ‘alignment’ — making sure our AIs’ goals coincide with ours, including avoiding negative outcomes — we probably haven’t thought about the problem long enough on a philosophical level to avoid being persuaded, and not always in a good way.

Barnes goes further, arguing that some ideologies are more suited to ‘persuasive AI’ than others:

We should therefore expect that enhanced persuasion technology will create more robust selection pressure for ideologies that aggressively spread themselves.

I wouldn’t argue with that. Indeed, we know from cults that a) they rely hugely on being able to persuade adherents to change behaviour (and disconnect from previous behaviour and those in that world) and b) the more radical the ideology, the more successful it can be. (Another take on ‘persuasion tools’ can be found here.)

I don’t think we’re any way near understanding what is really going on here, but I do think we need to connect the dots beyond AI and politics to realms that can help us better understand how we interact, build trust and bond with artificial entities. And to stop seeing chatbots as instruction prompts but as entities which we have known for nearly 60 years we are inclined to confide in.

- Ischen, C., Araujo, T.B., Voorveld, H.A.M., Van Noort, G. and Smit, E.G. (2022), “Is voice really persuasive? The influence of modality in virtual assistant interactions and two alternative explanations”, Internet Research, Vol. 32 No. 7, pp. 402-425. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-03-2022-0160 ↩

- Zarouali, B., Boerman, S.C., Voorveld, H.A.M. and van Noort, G. (2022), “The algorithmic persuasion framework in online communication: conceptualization and a future research agenda”, Internet Research, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-01-2021-0049 ↩

2 thoughts on “Chatting our way into trouble”